Difference between revisions of "World Pendulum"

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

| 38º41'N | | 38º41'N | ||

| 9º12'W | | 9º12'W | ||

| − | | | + | | 20 |

| 2677 +/- 0.5 @19ºC | | 2677 +/- 0.5 @19ºC | ||

| 80.5 +/- 1.0 | | 80.5 +/- 1.0 | ||

| Line 105: | Line 105: | ||

| 50º5.5'N | | 50º5.5'N | ||

| 14º25.0'E | | 14º25.0'E | ||

| − | | | + | | 150 |

| 2850 +/- 0.5 @25ºC | | 2850 +/- 0.5 @25ºC | ||

| 80.1 +/- 0.5 | | 80.1 +/- 0.5 | ||

| Line 126: | Line 126: | ||

| 14°56'N | | 14°56'N | ||

| 23°31'W | | 23°31'W | ||

| − | | 40 | + | | 40 |

| 2826,0 +/- 0.5 | | 2826,0 +/- 0.5 | ||

| 81.6 +/- 0.1 | | 81.6 +/- 0.1 | ||

| Line 133: | Line 133: | ||

| 4°36'N | | 4°36'N | ||

| 74°3'W | | 74°3'W | ||

| − | | 2650 | + | | 2650 |

| 2815,3 +/- 0.5 | | 2815,3 +/- 0.5 | ||

| 82.0 +/- 0.1 | | 82.0 +/- 0.1 | ||

Revision as of 14:49, 10 June 2020

Contents

Description

Rockets are launched to space from equatorial latitudes. This is due to the fact that the apparent weight of objects is gradually reduced from the poles to the equator. We will feel lighter at the equator than at the poles!

This small difference in apparent weight allows the same rocket to launch heavier payloads into orbit if launched nearer from the equator. For example, a Soyuz rocket launching into geostationary orbit from the French Guiana (5ºN) can carry 3 tons while it will only be capable of launching 1.7 tons of cargo when launched from Baikonur, Kazakhstan (46ºN).

The goal of this experiment is to find the value of the gravity "constant" through a constellation of pendulums placed in various latitudes and remotely operated, through the internet, by anyone.

It is expected that CPLP countries can contribute to this effort, bringing students, teachers and interested citizens closer together.

There are two different activities occurring simultaneously: (i) access, through e-lab, of the pendulums located in different latitudes and (ii) the construction and local operation in schools or at home.

Lisboa, Ilhéus, Faro e Rio de Janeiro were the first cities to contribute to the network in January 2013, making it possible for the first fits of experimental data to the theoretical equation within our project that describes how gravity changes with latitude to occur.

If you want to be a part of the World Pendulum network, please contact us by sending us an email.

Links

- Video Faro: rtsp://elabmc.ist.utl.pt/worldpendulum_ccvalg.sdp

- Video Lisboa: rtsp://elabmc.ist.utl.pt/worldpendulum_planetarium.sdp

- Video Ilhéus: rtsp://elabmc.ist.utl.pt/worldpendulum_ilheus.sdp

- Video Rio Janeiro: rtsp://elabmc.ist.utl.pt/worldpendulum_puc.sdp

- Video Maputo: rtsp://elabmc.ist.utl.pt/worldpendulum_maputo.sdp

- Video São Tomé: rtsp://elabmc.ist.utl.pt/wp_saotome.sdp

- Laboratory: World Pendulum in elab.ist.utl.pt

- Control room: Choose a location

- Grade: *

Who likes this idea

Experimental apparatus

The pendulum design used was based in Dr. Jodl's design[1]. Some minor changes were made to allow the same design to be easily replicated in high schools. The data concerning each pendulum is as follows:

| Physical sizes by place | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place | Latitude | Longitude | Altitude (m) | Cable length (mm) | Sphere diameter (mm) |

| CCV_Algarve/Faro | 37º00'N | 7º56'W | 10 | 2677 +/- 0.5 @23ºC | 80.5 +/- 1.0 |

| UESC/Ilhéus | 14º47'S | 39º10'W | 220 | 2705 +/- 0.5 @23ºC | 80.5 +/- 1.0 |

| Lisbon | 38º41'N | 9º12'W | 20 | 2677 +/- 0.5 @19ºC | 80.5 +/- 1.0 |

| Maputo | 25º56'S | 32º36'E | 80 | 2609.8 +/- 0.5 @27ºC | 80.5 +/- 1.0 |

| São Tomé | 0º21'N | 6º43'E | 50 | 2756.5 +/- 0.5 @29ºC | 81.8 +/- 0.5 |

| Prague - CTU | 50º5.5'N | 14º25.0'E | 150 | 2850 +/- 0.5 @25ºC | 80.1 +/- 0.5 |

| Barcelona - UPC | 41º24.6'N | 2º13.1'E | 55 | 2756.5 +/- 0.5 | 81.8 +/- 0.1 |

| Rio de Janeiro - PUC | 22º54.1'S | 43º12'W | 50 | 2826,0 +/- 0.5 | 81.6 +/- 0.1 |

| Praia - UniCV | 14°56'N | 23°31'W | 40 | 2826,0 +/- 0.5 | 81.6 +/- 0.1 |

| Bogotá - UniAndes | 4°36'N | 74°3'W | 2650 | 2815,3 +/- 0.5 | 82.0 +/- 0.1 |

| Panama city - UTP | 9°1.3'N | 79°31.9'W | 82 | 2825 + /- 0.5 @28ºC | 81.9 +/- 0.1 |

| Santiago - UChile | 33°27.5'S | 70°39.8'W | 552 | 2825 +/- 0.5 @27ºC | 81.9 +/- 0.1 |

| Valparaiso - UTFSM | 33°1'S | 71°37'W | 30 | 2827.5 +/- 0.5 @28ºC | 81.8 +/- 0.1 |

| Typical quantities | |

|---|---|

| String length (not counting the sphere) | 2705mm +/- 0.5mm |

| Sphere mass | 2kg +/- 75g |

| Sphere diameter | 81.2mm +/-1.5mm |

| String | Remanium(r) - Stainless steel (Nickel chromium)

- 0,4mm |

| Modulus of elasticity of string | ~200GPa |

| Oscillation period measurement system | Microprocessor with 7,3728MHz - 30ppm crystal

+ laser + PIN photodiode |

| Wire CTE (25-500ºC) (Coefficient of thermal expansion) | ~14 x 10-6 K-1 |

The experimental apparatus can be easily adapted to human operation, using a good chronometer, for local execution. The stainless steel structures can made in by brass or bronze for easier machining. The cable used can be replaced by a sport fishing steel cable and the mass can be replaced by a Olympic weight throw training weight, weighing 2Kg. A calibrated measuring tape should be used to measure the cable length, a few days after assembling the apparatus to allow for cable expansion.

Local partners

The pendulum[2], although one of the simplest systems commonly studied, is one of the richest in terms of physics.

In order to build a precise pendulum the most important factors are the precise measurement of the length of the cable, its quality, and of that of the pendulum supports. Selecting a mass between 1 to 4 Kg ensures that the pendulum's period error will be small enough for small local gravity changes (smaller than 0.1%) to be detectable, as long as a precise chronometer is used for timekeeping.

A local apparatus can be assembled using readily available materials and the local "g" values determined using such an apparatus can then be compared to the ones obtained through the remote pendulum constellation and the theoretical model.

Collecting this data through a social network will allow a more precise description of how "g" varies around the globe. The "World Pendulum" can be an important collaborative network for the dissemination of physics in schools.

Instructions on how to build such a pendulum are available in Precision Pendulum. The documentation of the development and construction of a pendulum are available in Precision Pendulum while the instructions on how to assemble it are available in Precision Pendulum Assembly.

If you want to be a part of the World Pendulum network, please contact us by sending us an email.

Physics

Determining gravity's acceleration in different parts of the globe raises questions about the importance of models in physics. It's possible to show that gravity's acceleration at sea level changes with latitude, and therefore a correction is needed for each individual location. This process allows us to demystify science and correct the existing "urban myth" around some physical constants that only are truly constant when some approximations are done. In this particular case, we will show how the introduction of successive corrections to gravity's "constant" will lead to values closer to those experimentally obtained.

Geophysical model

The starting point is the commonly used, constant, value of 9.81 ms-2. This is obtained by considering the Earth as being (i) a sphere (ii) that is not rotating. It's trivial to note that this model, due to the symmetry of the spherical form, does not allow for different values in different locations. This changes as soon as Earth's rotation dynamics and ellipsoid shape (flattening of the poles) are taken in account. These factors allow for gravity to change with latitude, and in fact these two factors are the two most important ones in this phenomena, outweighing every other effect, such as (i) altitude, (ii) tidal forces, and (iii) subsoil composition.

To demonstrate these finer aspects, gravity's acceleration must be determined in various latitudes around the globe distant from each other. Using the data collected, students can then ask themselves about how "constant" the value truly is and improve their intuition of gravity.

Experimental studies

Variation with latitude

As seen, the first possible study consists of using the remote pendulums to obtain a measurement of the local gravity acceleration for each location they're based in. Through considering (or not) several factors, it is possible to fit the data to a experimental description of the Earth using spherical harmonics (equation \eqref{harmonica-esferica}). This experimental work can be conducted using e-lab's pendulum constellation and our partner's pendulums.

Local determination

Following the instructions available in this wiki - Precision_Pendulum - or using any other kind of design that results in a rigorous apparatus, a local pendulum is built. It's then possible for measurements of local gravity to be made, as long as a good chronometer is used. Furthermore, it's also possible to contribute to the enrichment of the World Pendulum network's spreadsheet.

Tidal study

Using an almanac appropriate for the location, on can obtain the times of particular Moon/Sun alignments (full moon, new moon, waxing crescent and waxing gibbous). Plotting a graph spanning several months, one can try to verify and quantify the influence of tidal forces and Moon/Sun alignments in the apparent weight. It's possible to try and verify the correlation between Moon phases and changes in measurement of local gravity, by making a month or year-long study. Tidal effects are on the limit of detection by the pendulums of the e-lab constellation. For the experiment to be successful, it's necessary to be very rigorous on the time at which the experimental runs are made and some advanced numerical techniques, like the Fourier transform, need to by employed for the signal to be extracted from the data.

Analysis of wire torsion

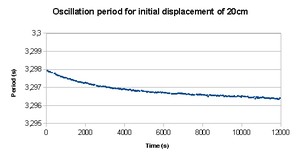

Those paying more attention will note that the speed of the mass changes due to wire torsion and due to the mass not being a perfect sphere. This is pictured in the image to the right. The pendulum can be studied taking into account the effect of the wire torsion (the use of Euler-Lagrange equations is recommended for this).

Uniformly accelerated circular movement

The speed of the sphere in the lowest point of the trajectory is determined by measuring how much time the laser beam is interrupted. Knowing the sphere diameter, it's trivial to determine the speed at the origin. From this, the maximum kinetic energy can be calculated and the launching height of the pendulum determined. The calculated launching point can then be compared with the real one.

CPLP as “latitude provider”

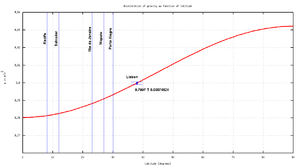

Language is an important nationality factor ("My fatherland is the Portuguese language.", F. Pessoa) and a simple way to define what is called brother countries ("países irmãos"). Only four languages are disseminated around the world, Portuguese being one of them. The Portuguese speaking community covers latitudes from ~30S to ~40N, almost a 75º span across the equator. Therefore, CPLP countries can help by being "latitude providers" (see Figure).

To conduct this world experiment, at least four spaced points are needed in order to have a proper fit. But due to the strong non-linearity of the equation, more points are needed to provide a suitable adjustment, in particular on the "knee" close to the earth’s equator. Brazil itself can provide almost four crucial points close to the equator (e.g. Recife 8º, Salvador – 12º, Rio de Janeiro – 23º, Porto Alegre – 30º) but lacks points with a latitude where the characteristic varies more strongly, the almost linear region around 30º to 60º, where Portugal can give two good points (e.g. Porto - 37º and Faro - 41º). Mozambique can contribute with 27º (Maputo) and S. Tomé e Principe or Brazil are both good choices to cover the equator. Angola could give complementary points to those acquired in Brazil, as the sensibility of the measurement is more pronounced close to the equator and the poles.

Data fitting

Available references [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] give a very good description of the mathematical model needed to fit the data. If all major factors are taken into account, gravity as a function of latitude is given by:

[math] g_{n}(\varphi) = 9.780 326 772\times[1 + 0.005 302 33 \cdot sin^{2}(\varphi) - 0.000 005 89 \cdot sin^{2}(2\varphi)] [/math]

where \(\varphi\) is the latitude. This expression is one of the best experimental approximations and results from the standardization agreement to adjust the World Geodetic System datum surface (WSG84) to an ellipsoid with radius r1=6378137m at the equator and r2=6356752m polar semi-minor radius. This formula takes into account the fact that the Earth is an ellipsoid and that there is an additional increase in the acceleration of gravity when one moves nearer to the poles, due to a weaker centrifugal force. Nevertheless the students could derive a non-harmonic, first order approximation by taking into account only centrifugal force. Then, as a second step, they could include the two other major errors, the centrifugal force and earth’s ellipsoid format.

The pictures shows the expected deviation from the “earth’s constant acceleration”, the real acceleration for each latitude. We have plotted the point already obtained with this apparatus in Lisbon and the marks over the expected latitudes for future partners. Of course these approximations do not include one important source of deviation from real data to the mathematical model, the experimental error, as we do not include the experimental source of error. However, those systematic errors could be under the expected precision needed (0,1%) for the former approximation if a careful design of the apparatus is considered. Nevertheless those errors must be discussed in advanced courses and their weight must be proved when considering the real pendulum.

Historical notes

The pendulum importance as the basis of clocks and chronographs was only overthrown when the Royal Society convinced the English parliament to create an award, ranging from 10k£ to 20k£ (equivalent nowadays to more than 3.5M€), for the invention of a chronograph that didn't depend on it. The time precision of pendulum based systems is only bettered by modern electronic systems.

In the discovery age longitude was determined with a high error, since clocks and chronographs were reliant on pendulums and these were very sensitive to ships rocking, suffering changes in frequency or even stopping. Local longitude was calculated by comparing the solar hour (or stellar hour) with the ship's clock time.

References

- ↑ World pendulum—a distributed remotely controlled laboratory (RCL) to measure the Earth's gravitational acceleration depending on geographical latitude, Grober S, Vetter M, Eckert B and Jodl H J, European Journal of Physics - EUR J PHYS , vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 603-613, 2007

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Physics for scientists and engineers, 5th edition, Hardcourt College Publishers, R.Serway and R. Beichner, 2000

- ↑ http://rcl-munich.informatik.unibw-muenchen.de/

- ↑ Nelson, Robert; M. G. Olsson (February 1987). "The pendulum - Rich physics from a simple system". American Journal of Physics 54 (2): doi:10.1119/1.14703

- ↑ Pendulums in the Physics Education Literature: A Bibliography, Gauld, Colin 2004 Science & Education, issue 7, volume 13, 811-832 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11191-004-9508-7)

- ↑ The exact equation of motion of a simple pendulum of arbitrary amplitude: a hypergeometric approach, M I Qureshi et al 2010 Eur. J. Phys. 31 1485(http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0143-0807/31/6/014)

- ↑ A comprehensive analytical solution of the nonlinear pendulum, Karlheinz Ochs 2011 Eur. J. Phys. 32 479 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0143-0807/32/2/019)